Strategy and The Strategist in the age of average

Note: this essay is inspired the work of a number of people, William D James, Jasmine Bina to name a few – Full link Below.

The strategist is an endangered species. You know this already. You’ve watched the layoffs, sat through the reorganizations where your role got folded into “growth marketing” or “brand experience” or whatever euphemism makes the CFO feel better about gutting the thinking capacity of the organization. The Miro boards still get populated, the “consumer journeys” still get mapped, the “brand territories” still get claimed like conquistadors staking flags in continents they don’t understand. But something essential is haemorrhaging out of the profession. Something that made it necessary in the first place.

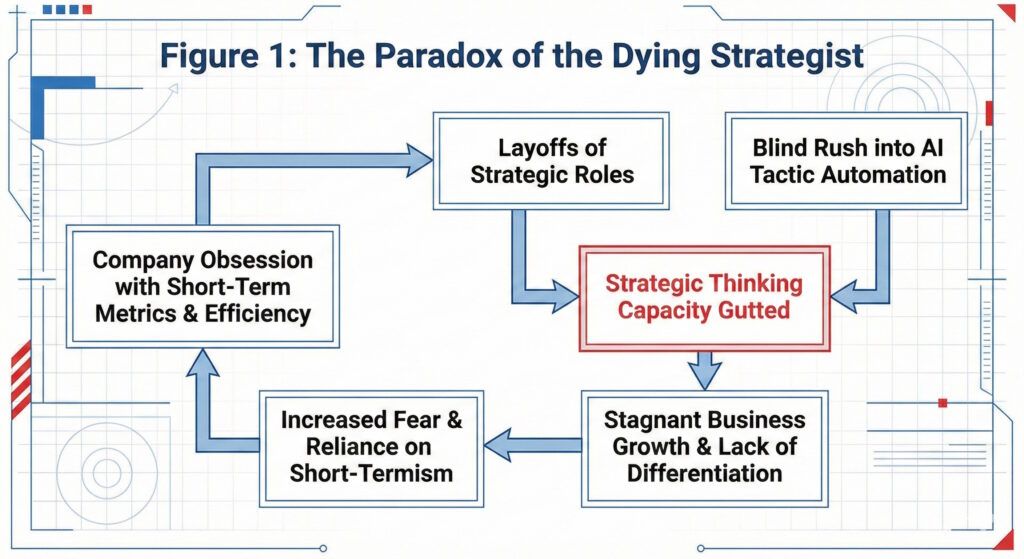

You can see it in the layoffs. Marketing strategy roles getting gutted while companies simultaneously complain about stagnant growth. You can see it in the metrics-obsessed short-termism that treats quarterly earnings like sacred scripture. Most of all, you can see it in the blind rush into AI, where businesses are automating tactics while forgetting that tactics without strategy is just expensive noise.

Here’s the paradox that should terrify you: businesses are stagnating precisely when they’ve abandoned the very function designed to prevent stagnation.

THE WHO: WHAT ACTUALLY IS A STRATEGIST?

Let’s start by clearing away the bullshit definitions. A strategist isn’t a planner who makes prettier decks. They’re not the person who does “the thinking” before the creatives do “the making.” They’re not junior account executives with fancier titles.

Grand strategy theorist William James offers a framework that cuts through the noise. Strategy emerges from five sources: individuals with distinct ways of thinking, departments with their own agendas, the intellectual ecosystem surrounding an organization, the prevailing spirit of the age, and a culture’s strategic inheritance. The strategist sits at the intersection of all five, serving as the synthesizer, the pattern-matcher, the person who can hold multiple contradictory truths in their head and find the productive tension between them.

Think about what Jasmine Bina calls “cultural strategy.” She argues that culture brands don’t win by being better, they win by moving the goalposts for everyone around them. The strategist is the one who figures out where those goalposts should move and why that movement matters more than incremental product improvements.

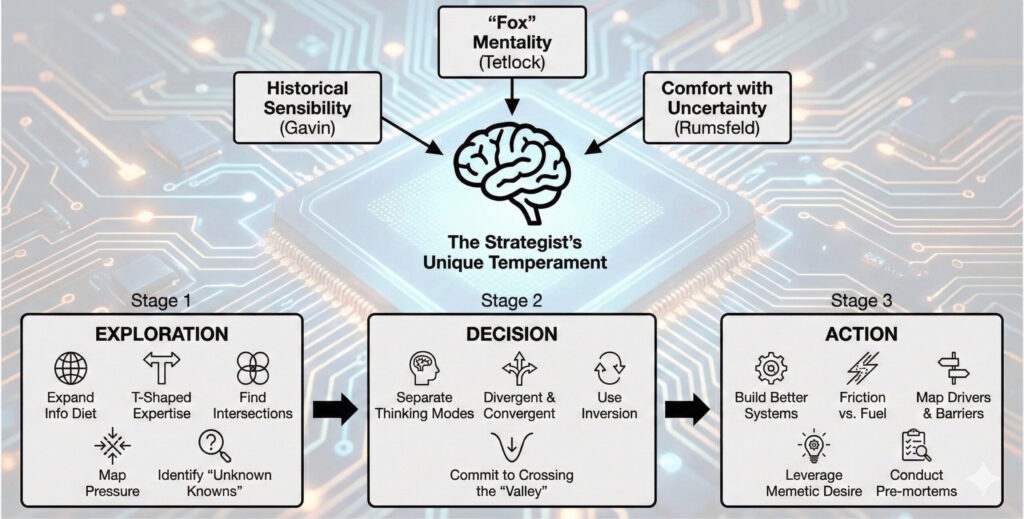

This requires a peculiar kind of mind. Francis Gavin calls it “historical sensibility,” an awareness of how the past unfolds into the present in complex, contingent ways. Philip Tetlock distinguishes between hedgehogs who pursue a single grand idea and foxes who entertain many possibilities, adjusting to new evidence. The best strategists are foxes with hedgehog conviction, people who can hold nuance and ambiguity while still making the hard choices that strategy demands.

Here’s the thing nobody wants to admit: this temperament is rare. Most people are uncomfortable with uncertainty. They want answers, not questions. They want certainty, not probability. The strategist has to be comfortable living in what Donald Rumsfeld’s matrix would call the “unknown unknowns,” the territory where you don’t even know what questions to ask yet.

THE WHAT: THE ACTUAL JOB OF STRATEGY

Roger Martin says it plainly in “The Big Lie of Strategic Planning”: most executives fear strategy because it forces them to confront a future they can only guess at. Worse, choosing a strategy means explicitly cutting off possibilities and options. That’s scary. Career-ending scary.

So they do what humans always do when scared: they create elaborate rituals that feel like strategy but aren’t. Strategic planning becomes an annual exercise in spreadsheet theatre. Vision statements get workshopped into meaningless platitudes that could describe any company in any industry. “We will be the leading provider of innovative solutions that create value for our stakeholders.” Sure. You and everyone else.

Real strategy is something different entirely. It’s about making integrated choices that position you to win in a specific way against specific competitors in a specific context. It’s about understanding the shape of the game you’re actually playing, not the game you wish you were playing.

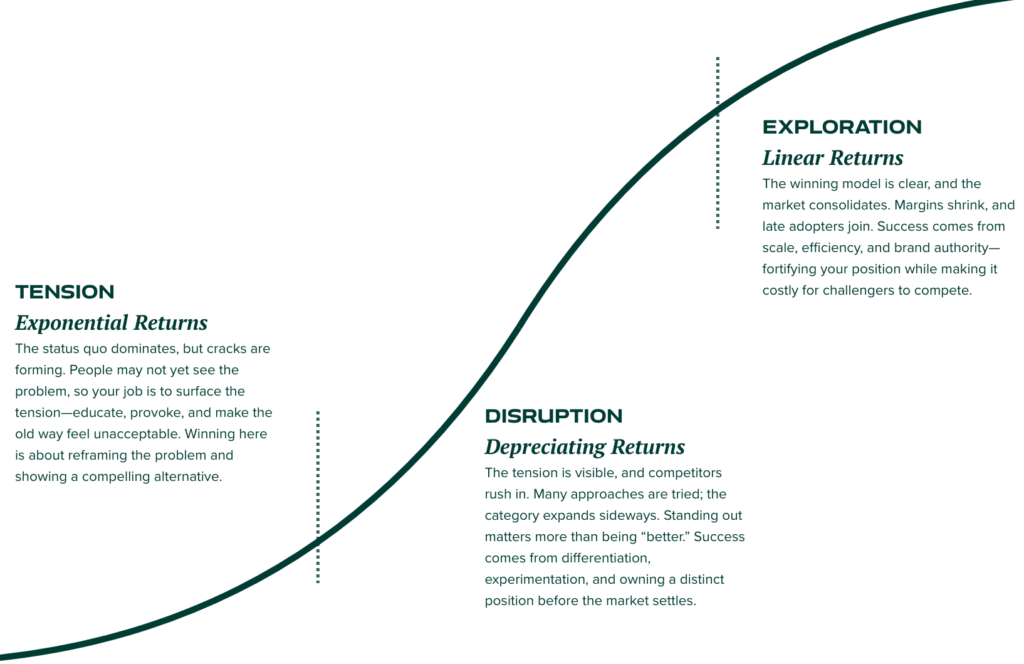

Bina’s framework for market phases is instructive here. Markets move through three predictable stages: Tension, Exploration, and Disruption. Each phase has its own rules for success. Deploy the right strategy at the wrong stage and you’re dead in the water. The strategist’s job is to read which phase you’re in and what that means for where you place your bets.

This is where most companies fuck up. They apply yesterday’s playbook to tomorrow’s game. They optimize for efficiency in a market that’s about to explode with new possibilities. Or they chase innovation in a consolidating market where the real opportunity is operational excellence.

The strategist prevents that kind of strategic myopia. They’re the person asking uncomfortable questions:

What business are we actually in? Not the business we say we’re in, not the business we were in five years ago, but the business we’re actually in right now given changing customer expectations, competitive dynamics, and technological shifts.

Where should we compete? Not where can we compete, but where should we compete given our actual capabilities and the structural economics of different market segments.

How will we win? Not how do we want to win, but how will we actually create and capture value in a way that’s defensible and sustainable.

These aren’t abstract questions. They’re existential. And answering them requires what David Rock calls managing with the brain in mind. You can’t force people into self-awareness through mandates and incentives. You have to create the conditions where they can see clearly, which means minimizing threat responses and maximizing the reward states that allow for creative, integrated thinking.

THE HOW: THE METHODS AND MECHANICS

Here’s where it gets interesting. Because strategy isn’t just about brilliant insights scribbled on napkins. It’s about having disciplined methods for generating those insights in the first place.

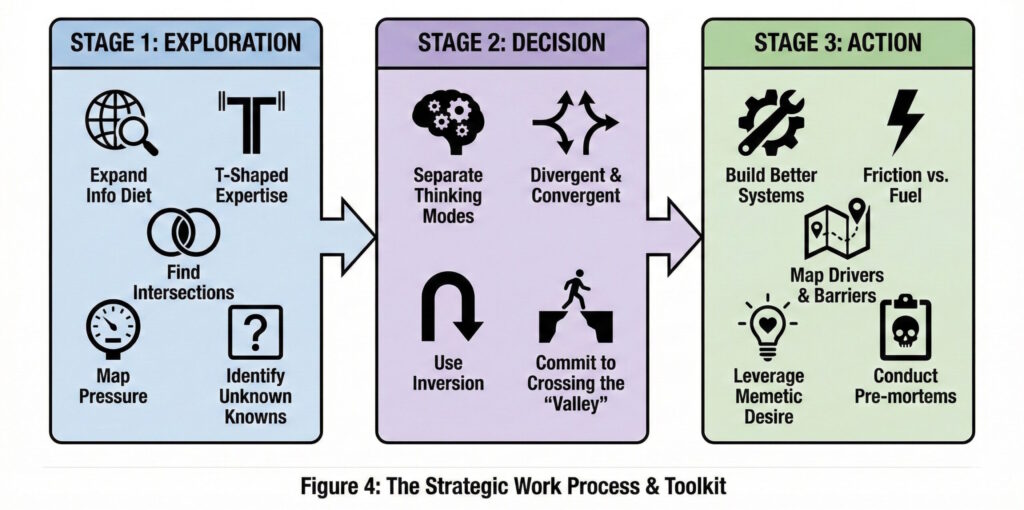

Bina breaks strategic work into three stages: Exploration, Decision, and Action. Each requires different mental models and different ways of working.

Exploration is about expanding your information diet. Most companies suffer from what you might call strategic malnutrition. They consume the same conference keynotes, the same industry reports, the same TED talks as everyone else, then wonder why their strategies feel derivative.

The best strategists build what Bina calls “T-shaped information diets.” Broad across topics, with deep vertical expertise in different domains. This isn’t accidental. It’s designed. Someone on your team needs to be obsessed with behavioural economics. Someone else needs to understand the technical architecture of AI systems. Another person needs to track cultural movements in youth subcultures.

Why? Because innovation happens at intersections. Every legendary disruption story is about taking an insight from one context and applying it to another. Netflix wasn’t created by people who understood video rental better than Blockbuster. It was created by people who understood subscription models and streaming technology and how those could recombine.

The strategist uses frameworks like Michele Gelfand’s tight/loose cultures to understand the cultural pressure in a market. Is it too rigid, with clear rules and low tolerance for deviation? Or too loose, with overwhelming choice and no guidance? The answer tells you what kind of value people will actually pay attention to.

You map the Rumsfeld matrix: known knowns, known unknowns, unknown knowns, and unknown unknowns. That bottom left quadrant, the unknown knowns, is where culture is primed for change but hasn’t had a chance to express itself yet. That’s your edge.

Decision is about converting exploration into choices. This is where most strategies die. Not from lack of insights, but from inability to decide.

The problem is that decision-making requires both divergent and convergent thinking, and most teams confuse the two. Divergent thinking is expansive, exploratory, judgment-free. You’re generating possibilities. Convergent thinking is evaluative, narrowing, choice oriented. You’re making commitments.

Mix them together and you get organizational paralysis. People self-censor during brainstorming because they know the ideas will be judged. Or they keep exploring indefinitely because they’re afraid of making the wrong bet.

The strategist knows when to shift gears. When new information stops making you feel confused, uncomfortable, or excited, that’s when exploration hits diminishing returns. Time to converge.

But converging requires courage. You must use tools like inversion, flipping the problem on its head to see it differently. Dallas-Fort Worth Airport didn’t speed up baggage delivery. They made the walk longer, so the wait felt shorter. Japanese bullet trains didn’t clean faster. They made the cleaning visible, so passengers understood why it took time.

You must understand local versus global maxima. Most companies get stuck at local peaks of “good enough” because reaching the next summit means crossing a valley of lower performance first. That trough is the switching cost. The strategist helps leadership commit to the climb instead of settling for mediocrity.

Action is where strategy meets reality and usually gets its ass kicked. Because executing strategy isn’t about having better plans. It’s about building better systems.

James Clear nails it: “We don’t rise to our goals, we fall to our systems.” Everyone at the starting line wants to win. Winners are the ones who built processes that make winning inevitable.

This is about friction versus fuel. When you want to drive a behaviour, your instinct is to add more motivation, more marketing, more incentives. But fuel only works if the path is clear. Usually, the fastest gains come from removing the friction that blocks action.

The strategist maps both. What’s driving the desired behaviour? What’s preventing it? You can throw a million dollars at a marketing campaign, but if your checkout process requires seventeen clicks and account creation, you’re fucked.

Then there’s memetic desire. Rene Girard’s insight that we don’t want things; we want to be like the people who have those things. We don’t want the boat; we want to be the person who has time to sail. We don’t want education; we want to be seen as successful. The strategist understands this distinction. They’re not selling products. They’re selling identity transformation.

And they use pre-mortems to pressure-test everything. Most teams plan as if everything will go right. The strategist asks the team to imagine the initiative has already failed, then work backwards to understand how. You’d be shocked how much foresight your team already has, gut instincts and pattern recognition that normally go unspoken. The pre-mortem gives those insights a forum.

THE WHY: THE VALUE STRATEGISTS CREATE

Now we get to the uncomfortable question. If strategists are so valuable, why are they being laid off?

Because most organizations have confused strategic planning with strategy. They’ve turned strategy into an annual ritual rather than a continuous discipline. They’ve reduced it to PowerPoint performance art rather than integrated decision-making.

Henry Mintzberg distinguishes between strategies that emerge and strategies that are deliberately planned. Most strategic planning exercises assume the world will cooperate with your spreadsheets. Actual strategy requires constant adaptation based on what you’re learning.

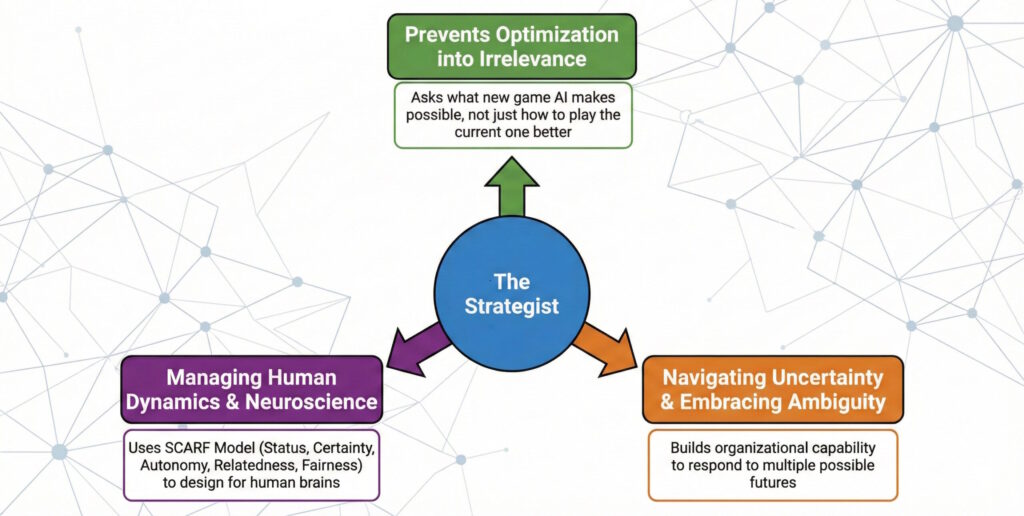

The value a strategist brings is this: they prevent you from optimizing your way into irrelevance.

Think about what’s happening right now with AI. Companies are rushing to automate everything touchable without asking what should be automated in the first place. They’re using AI to get better at tactics while their strategy remains fundamentally unchanged.

This is like using the internet to build a better fax machine. You’re missing the point.

The strategist asks: how does AI change the game we’re playing? Not how can we use AI to play the current game better, but what new game does AI make possible? What assumptions that were true in 2015 are no longer true in 2026? Where does that create white space for something genuinely new?

This is why Roger Martin’s criticism stings. Strategic planning has become a big lie because it promises certainty in an uncertain world. Real strategy embraces uncertainty. It doesn’t try to predict the future. It builds the organizational capability to respond to multiple possible futures.

The strategist creates value by holding space for ambiguity while still driving toward clarity. They help organizations make hard choices not because those choices are safe, but because they’re necessary. They protect against the tyranny of short-term metrics that optimize quarterly earnings at the expense of long-term positioning.

In neuroscience terms (David Rock’s SCARF model), the strategist manages the organization’s threat and reward responses. Status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, fairness. These aren’t soft skills. They’re the fundamental organizing principles of human brains in social systems.

When you reorganize without considering people’s need for autonomy, you trigger threat responses that make them worse at their jobs. When you create unfair compensation structures, you de-motivate everyone except the top earners. The strategist understands these dynamics and designs around them.

WHY THIS MATTERS MORE NOW THAN EVER

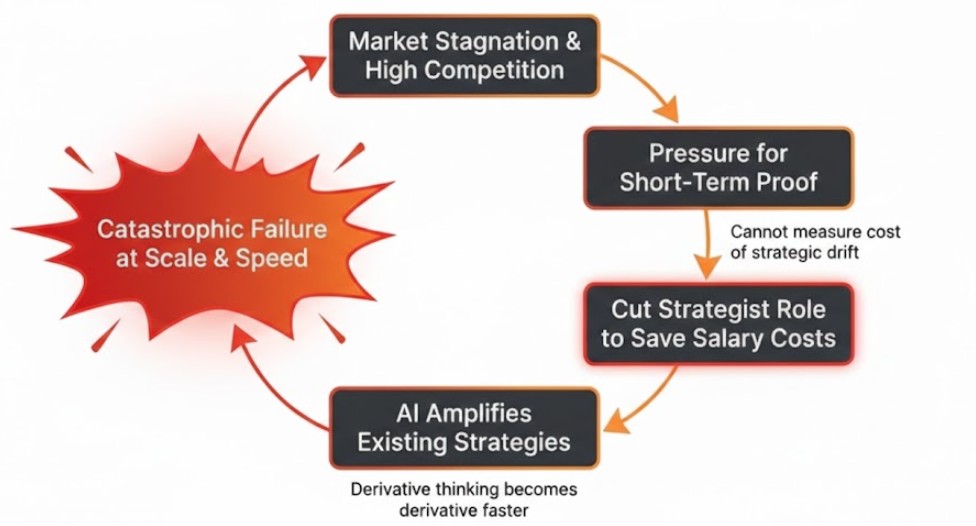

Here’s the cruel irony. Businesses are stagnating. Growth is harder to find. Markets are more competitive. Technology is changing faster than most organizations can adapt.

And yet they’re cutting the one function designed to navigate exactly this kind of uncertainty.

Why? Because in the short term, you can’t prove strategy prevented a disaster that didn’t happen. You can measure the cost of the strategist’s salary. You can’t measure the cost of strategic drift until it’s too late to fix.

This is compounded by AI. Not because AI is bad, but because AI amplifies everything. Good strategies become better. Bad strategies become catastrophic failures at unprecedented scale and speed.

If your strategic thinking is derivative, AI will help you be derivative faster. If you’re chasing the same signals as everyone else, AI will ensure you all reach the same mediocre conclusions simultaneously. If you’ve mistaken tactics for strategy, AI will make you incredibly efficient at doing the wrong things.

The strategist’s role becomes more critical precisely because AI makes the stakes higher. Someone needs to be asking: what question should AI even be answering? What frame are we using to understand this problem? What are we optimizing for and why?

These are human questions that require human judgment informed by historical context, cultural understanding, and the kind of lateral thinking that comes from truly diverse information diets and intellectual ecosystems.

Jasmine Bina talks about the three ingredients of play: freedom, safety, and separateness. When these overlap, you get the creative sandbox where breakthrough ideas emerge. AI can operate within that sandbox. But AI can’t create it. That requires human leadership and strategic framing.

The blind rush into AI without strategic clarity is like giving everyone in your organization a Formula 1 race car but no map, no destination, and no understanding of whether they should even be racing in the first place. You’ll go very fast in potentially very wrong directions.

THE STRATEGIST AS NECESSARY DEVIANT

So who is the strategist? They’re the necessary deviant in the organization. The person who questions assumptions everyone else takes for granted. The one who reads philosophy and anthropology alongside market research. Who understands that creativity and strategy aren’t opposites but different expressions of the same impulse toward novel problem-solving.

What do they do? They map the terrain of possibility and guide the organization through it. They convert uncertainty into actionable frameworks. They hold the tension between what’s working now and what needs to change for tomorrow. They create the intellectual architecture that allows everyone else to do their jobs better.

How do they do it? Through disciplined exploration that expands the information diet. Through frameworks that convert chaos into clarity. Through methods that separate divergent exploration from convergent decision-making. Through systems that make strategic behaviour inevitable rather than aspirational.

Why does this matter? Because without strategy, you’re just running faster on a treadmill. With strategy, you might get somewhere worth going.

The question isn’t whether you can afford strategists. It’s whether you can afford not to have them. Especially now. Especially when the pace of change makes yesterday’s playbook obsolete and tomorrow’s playbook hasn’t been written yet.

The strategist doesn’t predict the future. They build the organizational muscle to shape it. And in an age that’s forgotten how to think beyond the next quarter, that might be the most valuable function of all.

POSTSCRIPT: THE STRATEGIST’S PARADOX

You want to know the real test of a good strategist?

When they succeed, it looks inevitable in retrospect. The moves make perfect sense. Everyone agrees it was the right call. And because it worked, leadership thinks they could have figured it out themselves.

When strategists fail, it’s highly visible. The bet that didn’t pay off. The positioning that didn’t resonate. The reorganization that caused chaos.

So strategists operate in this perverse incentive structure where success makes them invisible and failure makes them culpable. Maybe that’s why they’re so easy to cut when times get tough. Nobody sees the disasters they prevented, only the costs they represent.

But here’s what I know: organizations that gut their strategic capability in pursuit of short-term efficiency invariably regret it. Usually about three to five years later, when competitors who kept investing in strategy have completely repositioned the market and your operational excellence means nothing because you’re excellent at an obsolete game.

By then, of course, it’s too late. Because you can hire strategists, but you can’t create strategic culture overnight. That takes years of discipline, debate, and accumulated organizational wisdom.

So before you nod along with the next round of “strategic planning is dead” think pieces, ask yourself: are you confusing bad strategic planning with the absence of strategy? Are you automating tactics while ignoring the fundamental questions of where to compete and how to win?

Because if so, you’re not just laying off strategists. You’re laying off your ability to think beyond the immediate, to see around corners, to position for a future that hasn’t arrived yet.

And in that gap between what you are and what you could be, someone with better strategy is already building the future that makes your present irrelevant.

That’s what strategists do. They prevent that fate. Or they did, back when we still valued thinking that couldn’t be reduced to quarterly metrics.

Sources and Citations: There are quite a few amazing thinkers and inspiring essays I read over the last few months – which compelled me to put this article together. The Authors and their work below:

Strategy Insight Explorer

Interactive directory of strategic frameworks & leadership concepts

Strategy Insight Explorer

Interactive directory of strategic frameworks & leadership concepts